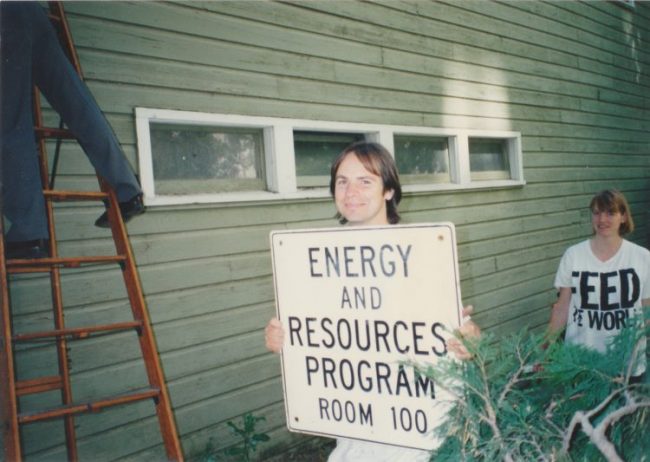

Photo: Williams posing outside of ERG’s old temporary building.

Why did you choose ERG, what made it unique for you?

In the 1980s I was working in Silicon Valley making speech synthesizer chips but wanting to do something more valuable in the world. I couldn’t decide what, and I didn’t like the silos that most jobs and academic disciplines put you in. My boss at the time had been a Ph.D. student at Cal, and he told me that ERG was the coolest program on campus. So I drove my VW up to Berkeley and met with John Holdren, who told me that the world’s big problems have no disciplinary boundaries, so your mind shouldn’t either. If the challenges you take on involve physics and philosophy and political economy and history, then learn what you need about all of them. That was music to my ears.

In the end, my ERG dissertation was on the political economy of science policy in China during the Cultural Revolution, as seen through the life of Fang Lizhi, a dissident astrophysicist who clashed with the Communist Party over cosmology. Much of the source material was in Chinese, and I had to translate it, so the dissertation took a long time to finish. It was well received by the China studies and history of science fields, but people outside ERG were usually stunned that I had worked on that topic while at ERG. People at ERG were not. They saw the connections.

What lessons, experiences, or opportunities from your time at ERG have you found to be most valuable in your career?

The classroom education itself. Back-of-the-envelope calculations as taught by John Harte and John Holdren. Hardly a day goes by that I don’t use those to quickly size up some problem. My research is based on box models. The science and engineering background has allowed me to work on the technical nuts and bolts of energy problems, but also in a strange way on its softer aspects. I’ve always felt like an outsider in the policy world, but the technical credentials I gained at ERG provided a kind of back-door access to policy-making. I spent much of the last decade trying to help steer the ship – of things like the Paris agreement, California energy policy, the US energy research agenda – from the engine room, when I wouldn’t have been allowed on the bridge.

The other great resource is the ERGies themselves, many of whom I collaborate with on a regular basis. The research team that produced the two main DDPP studies of the U.S. Pathways to Deep Decarbonization in the United States and Policy Implications of Deep Decarbonization in the United States, included many ERG alums: Margaret Torn, Andy Jones, Fritz Kahrl, Sascha Von Meier, Sam Borgeson, Rich Plevin, and Jamil Farbes. The group that I went to North Korea with in 1998 to build a small wind farm and do back-channel diplomacy was mostly ERGies – Peter Hayes, Chris Greacen, and David Von Hippel. The conference I hosted at USF last fall, called “The Land-Energy Nexus in Climate Change Mitigation,” was co-organized by Margaret Torn, Grace Wu, Rebecca Shaw, and Dan Lashof, with John Holdren as the keynote speaker. The USF energy program I now teach in was not only organized by Maggie Winslow, but has had a number of ERGies as advisors, including Tom Starrs, Ryan Wiser, and Nancy Radar.

One other thing ERG has been great for that is not about career: I met my wife and most of my closest friends at ERG.

What do you think are the most pressing environmental / energy issues today? What possible approaches or solutions do you find promising?

Climate change. My team has just completed a study of what it would take to return atmospheric CO2 concentrations to 350 ppm by the end of this century. That’s just about what it was the year I came to ERG, so it shouldn’t be so hard, right? But with CO2 already above 400 ppm and climbing, it will require not only decarbonizing the energy system but also removing CO2 from the atmosphere through biological or technological means. The good news is that doing all this is technically feasible and economically affordable. The tougher challenges are political and institutional, and there will be uncomfortable choices about things like land use and employment transitions. Bicycling and putting solar panels on your roof are not enough. Climate change is an industrial problem, and our country needs to have a grown-up conversation about comparative risks and the tradeoffs involved. Can we do it?

I say this is technically and economically feasible, but not without enormous effort. A Green New Deal that invests heavily in low carbon infrastructure could help address some of the challenges. Electricity system balancing with very high levels of wind and solar can’t be done solely with battery storage, whose technology characteristics don’t match the need for storage on weekly to seasonal time scales. New transmission and flexible electric loads, like hydrogen production and direct air capture, are a better fit, but will need investment and coordinated planning. Electrification of vehicles and building heating and cooling loads will require accelerating consumer uptake with policies and incentives. Nuclear power is still a potentially important resource but it needs not only technical improvements but a reboot of its relationship to society. Finally, there is the equity problem, which means that climate solutions must improve not worsen the lives of the poor if we expect developing countries, and our own country, to fully embrace them.

What advice do you have for prospective students, what can they expect at ERG?

Expect a lot, demand a lot, and give a lot. ERG’s culture consistently draws in excellent people and produces excellent results, and a big part of that is people challenging themselves and each other. Students need to participate in ERG’s governance, and not only through formal channels. ERG has always benefited from having students who were not timid nor overly awed by their professors nor so strategically career focused that they didn’t take time to ask big questions and pursue the answers outside authorized channels. By all means, take advantage of the candy store of great courses and great minds that is the U.C. campus.

We used to have a paper-copy ERG directory that said a little about each person’s areas of interest. They were very interesting to read, someone should dig them up. My entry read: “The Theory and Practice of Utopia.” That says something about the ERG mindset.

Any other comments?

ERG should frequently remind itself of the things that have made the program great. In my view, that means things like keeping the program small enough, sticking with the proven core courses, and not adding too many new requirements. For any outside audience reading this, ERG needs and deserves more external resources. Part of the solution is bigger than ERG – California needs to recognize that the U.C. system is the jewel in the state’s crown and invest in it accordingly. ERG also deserves way more support from the donor world, which draws on ERGies for a disproportionate share of the best thinking on energy and the environment.

Photo: Williams posing outside of ERG’s old temporary building.

Why did you choose ERG, what made it unique for you?

In the 1980s I was working in Silicon Valley making speech synthesizer chips but wanting to do something more valuable in the world. I couldn’t decide what, and I didn’t like the silos that most jobs and academic disciplines put you in. My boss at the time had been a Ph.D. student at Cal, and he told me that ERG was the coolest program on campus. So I drove my VW up to Berkeley and met with John Holdren, who told me that the world’s big problems have no disciplinary boundaries, so your mind shouldn’t either. If the challenges you take on involve physics and philosophy and political economy and history, then learn what you need about all of them. That was music to my ears.

In the end, my ERG dissertation was on the political economy of science policy in China during the Cultural Revolution, as seen through the life of Fang Lizhi, a dissident astrophysicist who clashed with the Communist Party over cosmology. Much of the source material was in Chinese, and I had to translate it, so the dissertation took a long time to finish. It was well received by the China studies and history of science fields, but people outside ERG were usually stunned that I had worked on that topic while at ERG. People at ERG were not. They saw the connections.

What lessons, experiences, or opportunities from your time at ERG have you found to be most valuable in your career?

The classroom education itself. Back-of-the-envelope calculations as taught by John Harte and John Holdren. Hardly a day goes by that I don’t use those to quickly size up some problem. My research is based on box models. The science and engineering background has allowed me to work on the technical nuts and bolts of energy problems, but also in a strange way on its softer aspects. I’ve always felt like an outsider in the policy world, but the technical credentials I gained at ERG provided a kind of back-door access to policy-making. I spent much of the last decade trying to help steer the ship – of things like the Paris agreement, California energy policy, the US energy research agenda – from the engine room, when I wouldn’t have been allowed on the bridge.

The other great resource is the ERGies themselves, many of whom I collaborate with on a regular basis. The research team that produced the two main DDPP studies of the U.S. Pathways to Deep Decarbonization in the United States and Policy Implications of Deep Decarbonization in the United States, included many ERG alums: Margaret Torn, Andy Jones, Fritz Kahrl, Sascha Von Meier, Sam Borgeson, Rich Plevin, and Jamil Farbes. The group that I went to North Korea with in 1998 to build a small wind farm and do back-channel diplomacy was mostly ERGies – Peter Hayes, Chris Greacen, and David Von Hippel. The conference I hosted at USF last fall, called “The Land-Energy Nexus in Climate Change Mitigation,” was co-organized by Margaret Torn, Grace Wu, Rebecca Shaw, and Dan Lashof, with John Holdren as the keynote speaker. The USF energy program I now teach in was not only organized by Maggie Winslow, but has had a number of ERGies as advisors, including Tom Starrs, Ryan Wiser, and Nancy Radar.

One other thing ERG has been great for that is not about career: I met my wife and most of my closest friends at ERG.

What do you think are the most pressing environmental / energy issues today? What possible approaches or solutions do you find promising?

Climate change. My team has just completed a study of what it would take to return atmospheric CO2 concentrations to 350 ppm by the end of this century. That’s just about what it was the year I came to ERG, so it shouldn’t be so hard, right? But with CO2 already above 400 ppm and climbing, it will require not only decarbonizing the energy system but also removing CO2 from the atmosphere through biological or technological means. The good news is that doing all this is technically feasible and economically affordable. The tougher challenges are political and institutional, and there will be uncomfortable choices about things like land use and employment transitions. Bicycling and putting solar panels on your roof are not enough. Climate change is an industrial problem, and our country needs to have a grown-up conversation about comparative risks and the tradeoffs involved. Can we do it?

I say this is technically and economically feasible, but not without enormous effort. A Green New Deal that invests heavily in low carbon infrastructure could help address some of the challenges. Electricity system balancing with very high levels of wind and solar can’t be done solely with battery storage, whose technology characteristics don’t match the need for storage on weekly to seasonal time scales. New transmission and flexible electric loads, like hydrogen production and direct air capture, are a better fit, but will need investment and coordinated planning. Electrification of vehicles and building heating and cooling loads will require accelerating consumer uptake with policies and incentives. Nuclear power is still a potentially important resource but it needs not only technical improvements but a reboot of its relationship to society. Finally, there is the equity problem, which means that climate solutions must improve not worsen the lives of the poor if we expect developing countries, and our own country, to fully embrace them.

What advice do you have for prospective students, what can they expect at ERG?

Expect a lot, demand a lot, and give a lot. ERG’s culture consistently draws in excellent people and produces excellent results, and a big part of that is people challenging themselves and each other. Students need to participate in ERG’s governance, and not only through formal channels. ERG has always benefited from having students who were not timid nor overly awed by their professors nor so strategically career focused that they didn’t take time to ask big questions and pursue the answers outside authorized channels. By all means, take advantage of the candy store of great courses and great minds that is the U.C. campus.

We used to have a paper-copy ERG directory that said a little about each person’s areas of interest. They were very interesting to read, someone should dig them up. My entry read: “The Theory and Practice of Utopia.” That says something about the ERG mindset.

Any other comments?

ERG should frequently remind itself of the things that have made the program great. In my view, that means things like keeping the program small enough, sticking with the proven core courses, and not adding too many new requirements. For any outside audience reading this, ERG needs and deserves more external resources. Part of the solution is bigger than ERG – California needs to recognize that the U.C. system is the jewel in the state’s crown and invest in it accordingly. ERG also deserves way more support from the donor world, which draws on ERGies for a disproportionate share of the best thinking on energy and the environment.

Here are the tricks you can use to meet girls offline. 1. Demonstrate confidence and openness rub ratings. When dating in real life, non-verbal cues can play into your hands. Remember open postures, steady (but not excessive) eye contact, and a genuine smile. They’ll do half the job: Introduce you to someone you don’t know.